How service can bring new meaning to design

- When fidelity is the measure of good design, it excludes those who can’t achieve the right fidelity

- The resources that contribute to fidelity – time, gender, race, class — aren't evenly distributed

- Rethinking who we consider designers opens up to design to include those design is for

- Instead of a process of creating an end product, we can look at design as a process of adding value

- When we centre design around service, design becomes an invitation to participate in shaping your own reality.

I really want to talk about what is fucked up about design.

It often starts with a question: “What do you do?”

When I say I’m a designer, the question that follows is: “Oh, what kind of design?”

And I start sweating.

Over time, I've realized that the question ‘what kind of design?’ is really asking, ‘what is the artifact or service that you're producing that people can engage with?’

And what I’ve also realized is that fidelity — fidelity being the level of detail, finish, polish, how bold it is, and how minimal it is — is the ‘design’ in question.

Fidelity is a very interesting topic, it’s this invisible line that helps to delineate hierarchy.

There are things that don't reach a certain threshold of fidelity. They get considered DIY, craft — Indigenous folks built it. Aliens built it.

Then there are things that are above this line of fidelity — that is design, innovation, art.

So what fidelity is, in its truest sense, is somebody's relationship to the resources needed to achieve that level of fidelity.

If you think about resources — time, gender, race, class — all of those things are resources that contribute to fidelity. And those resources aren't evenly distributed.

So when you think about what is design and who gets the chance to be a designer and how design shows up, if you're only looking at it through the lens of what is the end product or service that I can engage with — and then judging it based on fidelity — then that rules out so many people who should get a chance to participate in design.

When we started publishing Deem Journal, we wanted, initially, to help reframe design, and move design away from this idea of it being just outputs. We wanted to look at design as a process.

“Social Practice” is a form of art that is participatory and social in nature. Its goal is to create better outcomes, and it's not too concerned with the artifacts.

And not to diminish art, or move away from producing beautiful things, but to also say, ‘what can art do?’

Well if art can do that, what happens if design does that?

And so we started seeing design as a process of adding value. One in which the value that it adds also creates the conditions for people, communities, and systems to thrive.

We also realized designers aren't the only people who participate in the process of designing.

So many different people participate in design, but don't see their work as design — partly because of fidelity, partly because of not knowing the terms or the jargon, or having beautiful outputs.

And so we went on this voyage that we're still on. A journey to unpack: what does designing for dignity mean?

The first issue of Deem Journal featured Adrianne Marie Brown. She's a writer, she's a doula, she's an activist. She has a huge following, and when we asked her to be on the cover of our design publication, she hesitated and said, ‘I'm not a designer.’

But she took a chance on our hypothesis to say those who are working in different ways of creating conditions for people to thrive should also be cast under this umbrella of design.

And it was in that interview that she started to understand, ‘oh, I guess I can see parallels of how my work can show up in the design ecosystem.’

Deem has continued in that tradition ever since, exploring how we think about design through the lens of academia, equity and equality, placemaking, and climate change.

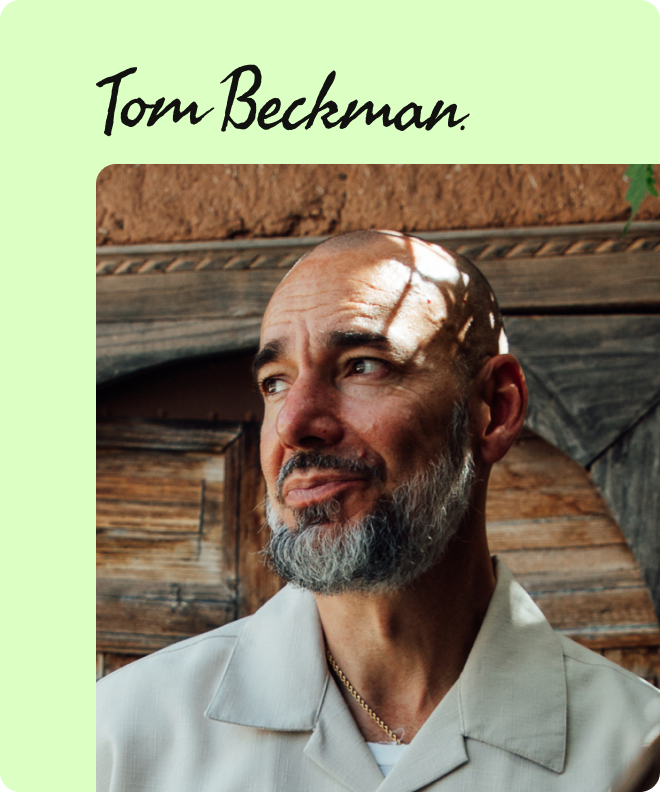

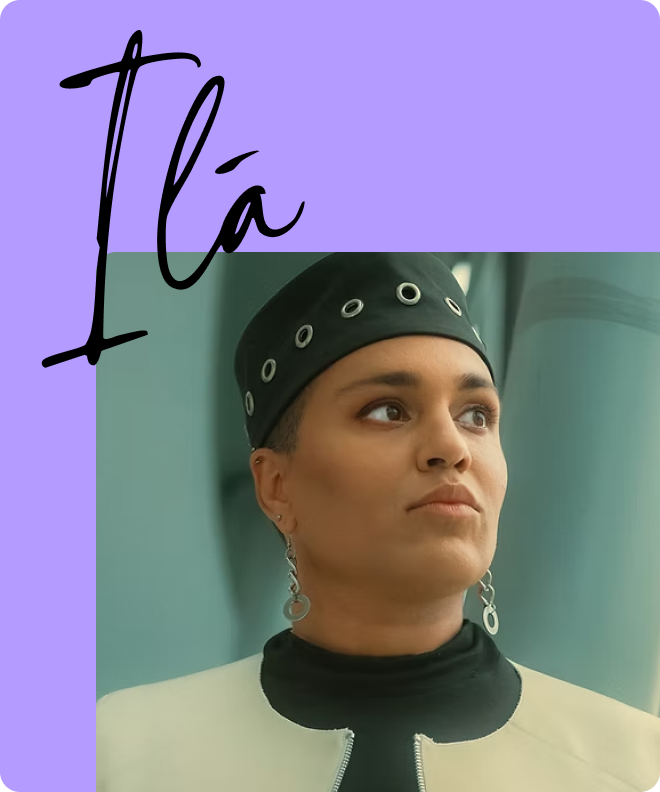

The type of people that tend to feature in the publication fall into two camps.

Firstly, there's disgruntled designers, designers who feel like design could and should be doing more for people and for communities.

And then there are change makers, people who don't care about design, they care about creating new paradigms.

They're urban farmers, they're doulas, they're activists.

And what we've seen is that when you bring these people together, exciting things start to happen.

When we centre design around service, design becomes an invitation.

It’s an invitation for people to participate in shaping their reality, with the hopes that if enough people feel confident and empowered to shape their reality, then people can feel confident to start to shape the world.